(Please note: This post is a revised and updated version of an

earlier article.)

Columbine, VTech, Tucson, Aurora, Newtown, hate crimes against Sikhs and Jews. Since 2006, there have been 232 rampage killings, an average of

one incident and five fatalities every two weeks. All too commonplace, mass

murder can strike any community at anytime without warning and claim any victim at random (source).

Every massacre elicits sensationalized news accounts as reporters,

pundits, and competing stakeholders assault our senses with hype, false

hypotheses, and self-serving narratives. Every massacre prompts a search for

clues to explain the unexplainable and incomprehensible. Perpetrators rarely live to disclose their

delusions or their motives in detail; more often they take their secrets to the

grave.

Years ago, I was researching delusional thoughts for a paper on

mental illness. Where do delusional thoughts come from? Are there patterns or

archetypes? Should rampage killings be considered impulsive acts, copycat

crimes, or manifestations of hitherto more complex phenomena as yet

unidentified?

We find examples of delusional thinking across a range of mental

illnesses - dissociation, bipolar disorder, pervasive developmental disability

disorders, the personality disorders, and schizophrenia, as examples. Delusions

are expressions of inner conflicts, drives, and memories that can take many

forms: Actual persons or historical events, personifications of painful emotions or traumatic memories, revenge personae,

violence in mass media, or voices in the head – all born of our culture and

made manifest in shocking crimes.

My research reveals this: Delusional thoughts are as much a

reflection of culture as a descent into madness. For lack of a better expression, I call these “cultural

artifacts” because they rise to the surface - not merely as dark impulses from

the subconscious mind - but from the Spirtius Mundi of culture

surrounding us. Simply stated,

culture shapes the way disturbed persons perceive and respond to their

delusions.

If you accept this finding - this influence of culture on

delusional thinking - then perhaps you might approach these murderous rampages from another perspective.

How does social stress correlate with violent crime? How do we

quantify and measure privation, depersonalization, and desperation - the kinds

of torments that find a path of least resistance in disturbed persons?

Recently, one of our readers commented:

Poverty

does not cause crime; it breeds despair. Mental illness does not cause crime;

it removes inhibitions and the ability to control dark impulses. Guns do not

cause crime; they enable people who despair to attain, if only for a moment, a

feeling of control, of superiority over others. That the feelings of control

and superiority often result in the taking of other's property, dignity, safety

and, far too often, their lives is not the result that they dreamed of. It is

the stuff of nightmares.

The incidence of mental illness is constant across all population groups – as constant as background radiation in the Universe. The

rate of violent crime in the mentally ill population is no different than the rate of

violent crime in the general population. Yet, America has a far higher

prevalence rate of violent crime, death by accidental shooting, and suicide by self-inflicted

gunshot than any nation in the world (source). Why? The ubiquity

of guns in America is a cultural artifact.

Doubtless, easy access to arms correlates with higher incidence

rates of violent crime. Our nation has 50% of all guns in circulation

worldwide and 30 times the murder rate compared with other industrialized

nations. Undeniably, gun culture is the vestigial relic of a frontier mentality

deeply imbedded in the American mythos – yet another cultural artifact.

Are rampage killings the only form violence perpetrated on the

American public? Hardly! Which is

worse:

·

A crazed gunman who kills 20 children at a clip? Or

merchants who sell junk food to children and consign them to lives of obesity

and diabetes;

·

Or the subliminal influence of violence in games marketed to

children and represented as entertainment;

·

Or manufacturers of automatic weapons that appeal, not to

legitimate sports enthusiasts, but to adult children reared on action toys who

project their self-image of manhood through the barrel of a gun;

·

Or reckless speculators who crash investment markets - leaving

millions of people in financial ruin;

·

Or a corporate CEO who orders massive layoffs - casting entire

families into panic and debt – who then rewards himself with a multi-million

dollar bonus.

Crimes of violence against people committed in the name of easy

money, fast money, and free enterprise: These too have become cultural

artifacts.

How often have we heard people in the news dismiss an alleged

transgression with this claim: “No laws were broken.” How often have we thought

to ourselves: The word ‘legal’ is not necessarily synonymous with the word

'ethical.' Legal acts - all too often considered immoral and

reprehensible - have become cultural artifacts.

During my parenthood years, I tried to teach my children the

relationship between responsibility and freedom. Parents reward good behavior

with confidence and trust - and punish misconduct with more supervision and

less independence. A reasonable proposition for raising children, I thought.

Yet, ours has become a society that fails to practice this relationship. Every

public controversy, and every perceived loss of freedom (whether imagined or real), represents a failure of responsibility.

What preoccupies our thoughts after the nightly news? We hear

about chicanery and corruption, inequality and injustice, abuse of our public

institutions, the lies and deceptions of persons who aspire to positions of

power and authority over us; of legislative deadlock and gridlock, and a public

abused by political hacks and henchmen. How often has the public interest been

held hostage by special interest groups and their lobbyists who hold our elected officials in thrall? The legalization of what we used to call ‘bribery’ and

‘graft’ have now become cultural artifacts.

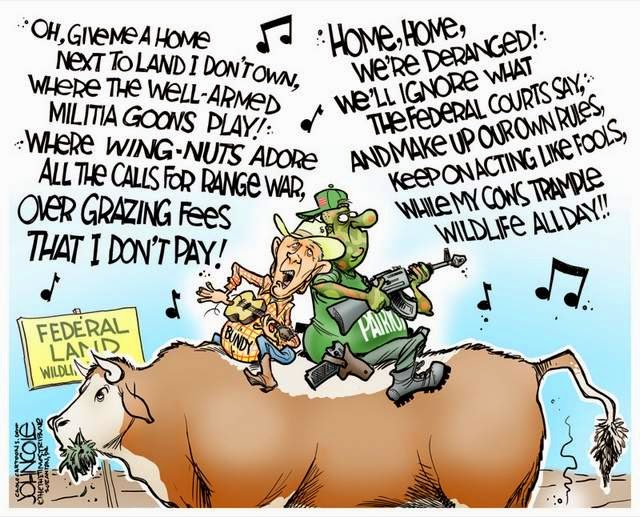

Reductio ad absurdum. After a weeklong silence following

the Sandy Hook massacre, Wayne LaPierre of the NRA responded with this

prescription: Fight fire with more firepower; place armed guards in every

school; arm the good guys to neutralize the bad guys. More guns!

Turn America into an armed fortress with self-appointed militias and

vigilantes in every city and town.

LaPierre offers not an imaginary dystopia but a real one – like

a bad Mad Max movie – creeping into our lives. Is the ubiquity of guns an

acceptable vision for our children and future generations? If you understand

the pervasive impact of ‘cultural artifacts’ on people, then LaPierre’s

prescription for fighting fire with more firepower is akin to pouring more

gasoline on a raging inferno.

We may talk about the dangers of easy access to automatic

weapons; about loopholes in our system of background checks and bullet holes in

our mental health establishment; about competing ideas of gun ownership versus

public safety. Perhaps these controversies, grave as they are, overlook more

fundamental questions.

In

exploring these relationships between madness and culture, and gun violence versus

the prerequisite need of society to secure public safety, I am reminded of the

moral dilemmas posed by Stanley Kubrick in his dark and disturbing film,

A Clockwork Orange.

It is the story of Alex, a punk, serial rapist, and murderer sentenced

to prison. Given a

choice between serving time versus gaining his freedom by taking the 'cure,' Alex opts for the operant conditioning cure that turns him into a ‘clockwork’ man – neutered of all violent impulses, a dehumanized shadow of his former self. Powerless against former victims and fellow punks who savagely beat and torment him, Alex notes with sarcasm: “I was cured alright!” In this ironic turn of the story, we are left asking ourselves: “But can society be

cured of its violent undercurrents?”

We practice brinksmanship but not citizenship. We equate freedom

with excess and excess with freedom. We facilitate overindulgence without

moderation or self-restraint. We covet freedom but spurn responsibility.

With each passing year, we drive all standards of civility, community and

accountability further into the wilderness. National conversations turn

fractious and fragmented. The high

ideals of secular democracy no longer bind us together. Perhaps the madness

in our midst reflects the accelerated grimace of a culture gone mad.

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold. How will more guns or less guns keep us safe when we have fostered a culture of ruthless greed, rampant corruption, and remorseless sociopathy? Perhaps these incidents of gun violence are signs and symptoms of a society in crisis.

The time has come to talk about our broken statues and battered books – these cultural artifacts that crash in the mind. Perhaps we should start a

national conversation at the very beginning by reaffirming those values of a

democratic republic whose mission and purpose is to secure “Life, Liberty

and the pursuit of Happiness.” The price of civilization is never cheap. We

demand the rights and privileges of full membership, but refuse to pay our

dues.